Bees just want to be bees. I’ve learned recently that, like most things in nature, a honeybee colony is most happy, calm and resilient when it’s left to do what it does best.

For bees, this means forage for nectar and pollen, raise a brood, and make honey. And bees want to do this in their own time, on their own schedule, and with the freedom to respond to each unique season. Which is quite contrary to how we currently manage bees. So what’s going on here?

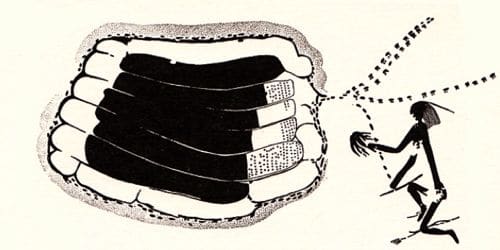

Ancient rock art showing beehive with honeycomb, beekeeper and bees! From ‘The Rock Art of Honey Hunters’ by Eva Crane

Our species’ treatment of the honeybee is a striking metaphor for our wider relationship with nature. In short, we started out okay, with a suitable amount of reverence, and then we progressively sought to bend the way of the bee to our wishes, convenience and ultimately, gross profit at the expense of all else. The result of this treatment has pushed the honeybee (a primary pollinator of most things we eat) to the point of collapse, and now we’re wondering what went wrong and how the heck to fix it. Sound familiar?

Until recently I thought beekeeping was pretty simple and straight forward. Don’t you just get a hive, plunk some bees in it, put it somewhere suitable, check it lots for disease, then harvest honey once a year? But once i started thinking, reading and chatting about it, I realised there are ways and there are ways…

Then I met Tim Malfroy (our beekeeper extraordinaire who we’re now running natural beekeeping courses with) and started to realize just how exquisitely amazing bees actually are. And how much damage we do when we manipulate their colonies to behave in a way that is convenient and profitable for us, but completely at odds with what bees need as a species. No wonder we’ve got multi-pronged crises on our hands with colony collapse disorder (CCD), rampant pest infestations and all sorts of scary things.

But I also learned that there is, as usual, a way of walking alongside nature here. A way of beekeeping that creates resilient, pest and CCD resistant honeybee colonies, and still gives us a yield of honey. And yet again, it’s all about observing, interacting and fair share.

To start at the start it’s best to acknowledge that a bee colony is a finely tuned super-organism with about 40 million years of evolutionary backup. Bees have been refining what they do for a bloody long time, and they’ve got things pretty much sorted. Understanding how they operate in a completely natural system is a good starting point for understanding their needs.

Bees colonise new locations by swarming. An exodus to a new promised land, if you like. And the ideal place for a new colony tends to be in a vertical hollow log, tree or similar – somewhere sheltered and insulated where the bees can raise their brood and be bees.

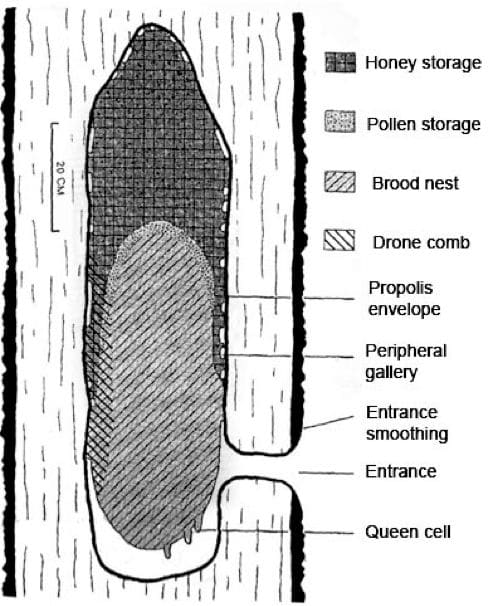

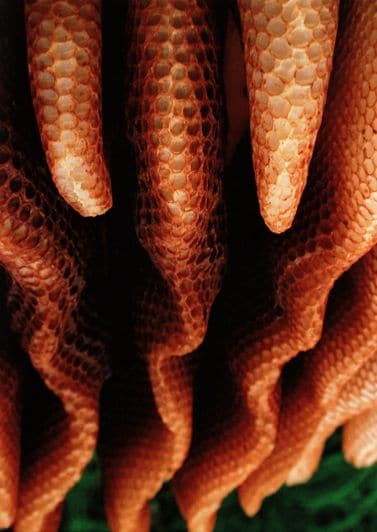

Within the new location, the bees busily dis-infect the cavity with propolis (which they make from tree sap) and get going making (or ‘drawing’) comb. The comb is made of wax, which exudes from the bees themselves. The comb is multifunctional – it’s hexagonal cells can house brood (baby bees), pollen, nectar (which becomes honey) or be left empty as part of the bees air-con system. The comb also forms part of the bees communication system, through vibration.

The shape of a bee colony in nature ensures the health of the brood by placing them in the middle. Above and beside the brood, the bees make a crown of honey-filled comb which insulates the brood from temperature fluctuations. Below the brood, the bees draw more comb, which will successively house brood and then honey as the colony grows and moves down through the cavity.

Bees create comb in response to the season: no two season’s combs are exactly the same – some years the cell size might be a little smaller or larger, perfectly responding to available nectar flows, fluctuations in temperature and other climactic factors which we can’t predict, but somehow the bees can.

At any one time, a single honeycomb can contain brood, pollen and honey, all in different cells. Generally, as the colony moves down through the space, the upper combs get dedicated to honey only, becoming both the bee’s insulation and also winter food store for times when nectar and pollen are scarce.

This insulation thing is really important: the center of a bee colony needs to sit at about 35 degrees centigrade at all times for the health of the colony and the brood. Yes, that is 35 degrees, year round, rain, hail or shine. And yes, bees are insects, so there’s no body heat going on there. So how do they do it? Well, we think it’s done via ‘thermo-regulation’ – ie friction – lots of bees moving their heads very fast to maintain the temperature within the hive. Which takes a lot of energy, as you can imagine. My neck is sore just thinking about it.

Rather than leaping into a lengthy discussion of my new found knowledge about the joy and utter amazingness of bees, I’ll leave it there for now. But the above, i have learned, is the crux of what makes for a healthy bee colony: honey above, brood below, room to extend beneath and constant temperature.

So natural beekeeping (as opposed to not-quite-as-bad-as-conventional beekeeping, sometimes called by the same name) is all about letting bees be bees, and harvesting surplus honey when it is available. In the meantime, you get fantastic fertility from having so many pollinators around, and you’re creating resilient colonies which are disease resistant.

I won’t go on about conventional beekeeping here and how far it’s practices differ from a bee colony’s natural state. Suffice to say many researchers are now questioning whether our currently accepted ‘regular management’ of beehives (like opening the colony once a week, thereby destroying the central temperature for days on end and making the colony work overtime to regain an even 35º) actually creates and exacerbates disease, stress and CCD within bee colonies. Instead I’ll focus on beekeeping that fosters resilient honeybees and honey production.

Warré beekeeping is a method developed by a french monk born in 1867 (Abbé Émile Warré) which strives to create a hive environment which is ideal for bees and also gives a honey harvest. I expect I will be waxing lyrical about this method in times to come, but in short, from what I’ve gleaned so far, Warré beekeeping has the following characteristics:

Top bar hives: the top bars in each bee box (or ‘super)’ provide a starting point for the bees to draw comb off. Sometimes they have a small strip of foundation (wax comb) to get the bees going, but for the main the bees are free to create their own comb shape and cell-size.

No Frames: regular beehives consist of frames, which define the limits of each comb. Regular frames also have a ‘foundation’, the hexagonal pattern that forms the basis of the comb cells. These fabricated cells are a set size and maximise honey production. By removing frames and foundation from the mix, the bees are allowed to define their own comb structure and cell size.

Roof: apart from looking very funky, a Warré hive roof helps insulate the colony below, allowing for airflow. An insulated roof helps reduce the colony’s stress and makes them more comfortable.

Smaller boxes: The box size of a conventional hive (known as a Langstroth hive) is based on the limit of what a bee colony can bear (and what crates were available to Langstroth when he started selling the hives which came to form the international standard on hive size). Warré hives are sized smaller to better suit the bee colony, and by default are better for the beekeeper because they aren’t so heavy ( a box full of honey is quite a load).

Nadiring: This is the process of adding supers to the bottom of the hive, not to the top. By adding a box to the base of the hive, the colony is allowed to ‘grow out’ of their top box, leaving it full of honey as they move down the created cavity. Again, this creates far less disturbance for the colony than conventional ‘supering’ where boxes are placed on top, forcing the colony to re-insulate their cavity by filling the new box above with comb and honey (remember a colony aims to fill the space above and around the brood with honey).

Minimal maintenance: the Warré method aims to minimise interference with the bee colony, ideally inspecting it only once a year, in autumn, right before harvesting the honey. A minimum of inspection means a minimum of disturbance for the colony. This is obviously at odds with conventional advice which advocates ‘pulling a frame’ from the center of each and every box once a week to ‘check for disease’. Tim Malfroy likened this practice to having open heart surgery once a week to check your heart is ok. Hmm. Maybe there’s other ways to ensure ongoing health of a bee colony, without destroying its core temperature?

No toxic chemicals: you would probably be surprised to find out how many toxins are painted, sprayed and applied to most beehives in the name of keeping them disease free. The bees, of course, do not like toxins. They frantically propolise what they can to disinfect their home, and the rest they absorb, and pass on into the honey and their brood. Warré hives are usually sealed with linseed oil and not painted. And the theory is to let the bees alone as much as possible to allow them to deal largely with bouts of pests and disease as best they can, without our ham-fisted chemical help.

In essence, if one can create an environment for a bee colony to exist in that is eminently suitable and does not stress the bees out in any way, that bee colony has a better chance of being resilient, disease resistant and producing darn fine honey. If the enterprise of keeping bees is seen as working in concert with the colony, rather than pushing them to their limits in the name of maximum yield, everyone benefits. It’s just common sense, really, but not widely practiced (yet).

We’re looking forward very much to Tim Malfroy arriving one day soon with 3 Warré hives which will live at Milkwood, and we’re eager to be good bee friends with the colonies within (bee-friends? bee-parents? I wonder what the appropriate term is). I’m looking forward to learning ‘the way of the bee’ and letting them do their thing in our top food forest and for miles around. I’m also looking forward to the amazing honey they will create, some of which I will hopefully get to harvest this autumn…

Here are some resources that Tim Malfroy recommended to us on natural beekeeping:

- The Warré pages at BioBees.com – includes a download of Warre’s recently translated text Beekeeping For All (L’ Apiculture Pour Tous, 12th edition).

- The gift of bees – a free e-book by Slow Food Foundation

- The buzz about bees: biology of a superorganism – freely available at googlebooks. One of the best text on understanding these fascinating creatures.

- The Barefoot Beekeeper – a great book on top-bar beekeeping.

- Malfroy’s Gold is Tim’s family website. They sells amazing honey, honeycomb and beeswax products from Bathurst in NSW, and do a bunch of Farmer’s markets in the Blue Mountains and Sydney as well. Yummo.

So when you get a moment in this busy world of ours, have a look and a think. I don’t need to tell you how essential healthy pollinators are to our existence. But i do think it’s worth getting a sense of how we can play a role in perhaps creating resilience for this crucial species.

Oh yes and of course there’s our Natural Beekeeping courses we’ve started running with Tim Malfroy, in Sydney and soon at Milkwood – as far as we know, these are the only warre-focussed beekeeping courses in Australia, and they are awesome!

I’ll also be posting the full experience of being a enthusiastic novice Warré beekeeper as I progress along this fascinating path. Wish me luck and very few stings?

Exciting, I am keen to get bees, I would have LOVED to get them this year, but I think it’ll probably be next year. I want to build a horizontal top bar hive. Love the idea of natural beekeeping, and letting bees do their thing instead of OVER caring for them and actually stressing them out so much. Good luck with it. Love that photo of the comb towards the end of the post.

Great post! May Dad and I have recently converted our conventional hive into a Warre; if you’re on facebook, you can see some of the pictures here:

http://www.facebook.com/album.php?aid=452918&id=655525695

Thanks so much for this great post! I’ve been getting more and more interested in honey and beekeeping methods as my palette has changed from detesting to loving the stuff. I notice such a huge difference just in taste between commercially made honey (by those poor stressed bees) and the local, more natural beekeepers.

Good luck and I hope you have a great honey harvest!

Bees! I will be even more excited to join you next Feb for the internship!

Wow this is interesting reading. I’ve got 1 hive myself and I’m about to try and create a second using a queen embryo from my first. I also don’t use the foundation and let the bees make their own, but I do use frames, but again, not as many in a super as ‘proper’ beekeepers do. Love reading your email infos.

Thanks, Wendy! Yep frames with no foundation are a good go-between. You could also try taking the bottom off the frame – that would (apparently) make them happier and less likely to connect the space between the bottom of that frame to the top of the next one, too.

Wow, that was all so very informative and intersting to read. I REALLY want bees. But I live in the Blue Mountains and was told that it was to cold here for me to be able to actually collect honey. Is that true?

Ronnie that may be the case for native bees, but for European honeybees you can definitely harvest honey if you’re in the blue mountains – and you are surrounded by one of the most densely packed nectar sources in Australia to boot! We are colder for longer than the Blue Mountains, and it is possible here…

Wonderful, exactly what I was looking for (as opposed to those conventional/not-as-bad-as flimflam sites). I’m a new mommy, and my son seems to have a connection with bees, which has made me think back over all the experiences I have had with them, and I feel Bee co-existence is in our future. This is lovely reading, thank you.

you’re welcome, Megan – best of luck with your bee journeys…

Thanks for sharing your story, we also want to keep bee’s in a bee friendly way and have enjoyed reading your journey.

Hi Kirsten! I happened upon this page in an interesting (and sadly annoying) way but am very happy I did because I will be following from now on! I, along with another friend, bought a Warre hive last year and bought a nuc from a regional beekeeper who is extremely knowledgeable. They are doing great and have been surviving this first winter really really well. I’m so proud <3. I recently bought another Warre hive through an Open Source Beehive Project Indiegogo project and went back to the same guy to purchase another nuc. However, this time I was lambasted… Read more »

Ugh – that’s no good. Sounds like your beek had some bad experiences with folks thinking beekeeping was simpler than it is and not doing a very good job, hence the crankiness.

Try getting hold of some packaged bees – literally, a package of bees – rather than a nuc hive – these can then be shaken into a warré hive easily. Keep going! The bees need more determined stewards like yourself 🙂